Fake News and Disinformation in Yemen’s Conflict

6/05/2021

Against the backdrop of Yemen’s conflict and its litany of socio-economic ramifications—famine, disease, blockade, worrying religious and geographical divisions—are the media wars, which rage across the country and the broader region. As different outlets and networks battle for hearts and minds, Yemenis everywhere are faced with the challenge of finding accurate and reliable information regarding the war and other critical domestic issues.

Providing Yemenis with access to neutral news and increasing opportunities for local journalists to develop their skills is an essential component of Yemen’s peacebuilding process. Survey research conducted in the past year by DT Global and ARK Group indicates that the extreme polarization of Yemeni media is exacerbating the ongoing conflict and adding to the many challenges that Yemenis face in their day-to-day lives.

In a survey conducted in August 2020, 705 respondents from seven governorates—Taiz, Ibb, al-Hodeidah, Marib, Aden, Abyan, and Hadhramaut—responded to questions about the local media environment, the phenomenon of fake news in Yemen, and ways to improve their communities’ access to reliable information.

While not fully representative, their responses offered a glimpse into Yemen’s current media landscape and the key challenges Yemenis face when trying to learn about events in their own country and abroad. Like most media consumers worldwide, Yemenis are inundated with politicized and contradictory reports on current events, both in local and social media.

Disinformation in Yemen

Survey findings indicated that virtually all Yemenis believe that fake news is a problem in their country. The majority of respondents reported hearing or seeing a piece of news they consider to be fake multiple times every week. The most commonly misreported stories in local media are those covering military developments, Yemen’s peace process, and the provision of basic services. The most frequently misreported topics varied depending on governorate. Respondents in al-Hodeidah, for example, believed that the presence of foreign powers in Yemen was frequently misreported, while respondents in Aden said military developments and basic services were often misreported by Yemeni news outlets. Health news, including news on COVID-19, ranked high on the list of misreported stories and at the time of the survey, more than 70% of respondents felt that local coverage of the coronavirus was politicized.

Since the start of the pandemic, news of the coronavirus has been widely underreported and misreported in local Yemeni media. Poorly equipped hospitals and weak government institutions in many areas mean that statistics about the coronavirus are often unreliable. In Spring and Summer 2020, there was a lack of knowledge about COVID-19, which not only sparked fear and uncertainty, but also allowed some political parties to instrumentalize the virus for their own aims. Due to the efforts of local NGOs, reliable information about the virus’s origins, symptoms, and means of prevention have become more accessible.

Despite this increased knowledge in Yemen about COVID-19, conspiracy theories about the virus have surfaced again as a second wave now spreads across the country, infecting large numbers of citizens and high-ranking officials. What remains unclear is how many Yemenis have been infected or died from COVID-19, since reliable statistics are absent, especially in northern governorates.

Issues surrounding Yemen’s conflict, including military and civilian casualties and territorial control, are often the subject of fake news. At the time of the survey, respondents in Marib reported the highest rate of observing fake news, with 42% of participants saying they see or hear fake news once a day or more. This high rate of disinformation in and about Marib is possibly linked to military action in the governorate, where the Houthis are currently making a push to seize the strategic city.

To avoid falling for fake news, respondents said it is important to follow official news sources, to look for multiple outlets reporting the same story, and to pay close attention to contradictions between outlets of opposing political affiliations. They said it can be helpful to look at how the piece of news is being reported. Exaggerations and biased language, they explained, may indicate that a piece of news is fake. Other respondents said they recommend following international news outlets, such as BBC Arabic, for neutral coverage, or to look for outlets reporting live from the site of events.

Trust in specific platforms and outlets

Seventy percent of all survey respondents said that the quality of Yemeni news outlets has declined in the past five years, and this had led Yemenis to rely more heavily on foreign news organizations. The responses indicate that Yemenis are aware of the biases inherent to local media outlets forced to operate during war, and perhaps the need to seek out impartial international outlets for more objective reporting. The use of social media to share news in Yemen has grown increasingly popular among Yemenis, especially with the youth demographic, as traditional media outlets are forced to take sides in the conflict and in doing so lose the general public’s trust.

The most reliable Yemeni outlets nationwide were reported to be Yemen Shabaab, Belqees, and Yemen Today. The ranking of each outlet’s reliability varied significantly between governorates, meaning that these top three outlets were also frequently ranked as highly unreliable by respondents in certain regions. For instance, both Belqees and Yemen Shabaab, which tend to promote the views of Islah, were ranked as the least reliable outlets by many respondents, as was the Houthi outlet Al-Masirah. Within governorates with a strong Houthi presence, Al-Masirah and Al-Sahat were reported as two of the most reliable local outlets. Older respondents and men tended to rank Al-Masirah and Al-Sahat as more reliable, while youth and women preferred Yemen Shabaab.

The top three most reliable international news outlets were BBC Arabic, Al Arabiya, and RT Arabic. However, just like the rankings of local Yemeni outlets, the perceived reliability of these channels varied drastically depending on the area being surveyed and the dominant political parties based there. Governorates with a strong Houthi presence—including Al-Hodeidah and Ibb—ranked Saudi-owned Al Arabiya as one of the least reliable outlets, while southern governorates such as Aden and Abyan ranked it as one of the most reliable. Similarly, respondents in Aden—where the UAE-backed Southern Transitional Council enjoys considerable support—reported a deep distrust of the Qatari-owned outlet Al Jazeera.

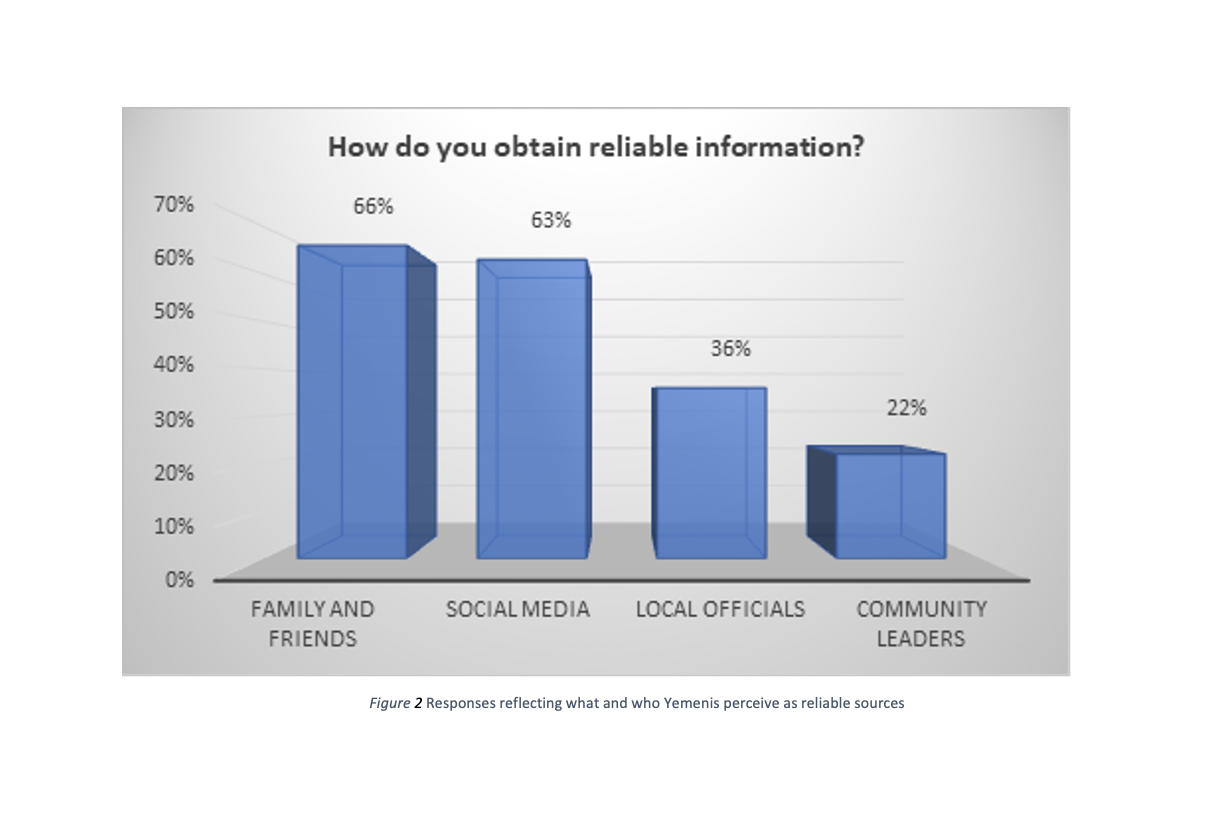

Countrywide, the least reliable sources of information were reported to be WhatsApp, local officials, and Facebook. Meanwhile, television, news websites, and friends and family are considered to be the most reliable. These rankings were shared consistently across gender and age group, and they demonstrate that Yemenis trust their family and social networks the most and that these relationships remain compact.

Censorship

The role of Yemen’s local authorities in censoring and regulating news is a contentious topic. Last year’s survey and other research activities conducted by DT Global and ARK Group show that Yemenis are divided over the role that local authorities should have in controlling the media’s coverage of events. When asked simply whether or not Yemen’s news should be censored more, 57% of all respondents agreed or strongly agreed that it should be.

Survey respondents in the governorates of Aden and Abyan overwhelmingly supported increased censorship of media (97% and 94% of respondents, respectively). The majority of Hadhramis surveyed also said Yemen’s news should be censored. Most respondents in the northern governorates of Ta’iz and al-Hodeidah expressed the opposite belief, saying they disagreed or strongly disagreed that Yemeni media needs more censorship.

There are a number of possible explanations for this disparity between governorates—those locations that do not welcome censorship may generally be distrusting of the official bodies that would be charged with regulating media. Alternatively, governorates that report a desire for more censorship may feel frustrated with the local media environment (such as its polarizing impact and the spread of disinformation) and they believe that an official body overseeing media production could improve this.

Ways to improve and further recommendations

In order to improve Yemen’s media landscape and increase trust in local outlets, respondents said they hope to see the establishment of politically neutral news outlets as well as more training for local journalists. Other respondents believed that increased media awareness among average Yemenis—whether through trainings or improved education—could help citizens identify and reject disinformation.

Aside from issues of fake or unreliable news stories, Yemenis also face a number of challenges in simply accessing the information that is most important to them. Respondents of all ages expressed a desire to see more coverage of issues relating to basic services, including electricity and infrastructure. Others also said they want to see more stories that tackle government corruption and objective coverage of military developments and health news. In northern governorates, respondents most wanted to see reporting on the peace process and prisoner exchanges, while southerners reported the greatest need for coverage of basic service provision.

Respondents provided useful pointers for the donor community on how improvements in local electricity and internet access can increase Yemen’s media landscape more generally. Many areas of Yemen suffer from a partial or total lack of access to grid electricity, along with internet connectivity issues that can be attributed to both the absence of reliable electricity and prohibitively expensive internet packages. The majority of surveyed respondents in every governorate reported that a lack of electricity or internet prevents them from accessing news and information. This is an especially serious problem in al-Hodeidah, where 100% of respondents said that they are prevented from accessing news due to lack of internet connectivity. Financial and infrastructural support provided by local and international organizations could have an immediate positive impact in increasing Yemenis’ access to information.

One male respondent from Sanaa explained that increasing the public’s trust in the peace process, and following through with the required steps, will likely lead to greater involvement and support at the community level. Another respondent from Marib explained that “increasing the local population’s ability to receive the required services is necessary as many locals are not sure where to seek help.” Thus, the donor community can support media efforts at informing Yemenis of how to access basic services and engage the community in the peace process through honest reporting.

Respondents in Hadhramaut said that more frequent interaction with local authorities would increase their access to reliable news. The lack of trust in local officials in other parts of the country should be examined by donor entities, and continue their support at strengthening institutions and transparency. The promotion of transparent behavior by political figures through media platforms could result in greater accountability.

Finally, women showed greater interest in neutral information and diverse content. A respondent from al-Hodeidah said that she would like to see more programs from Yemeni outlets geared towards children, as a way to help them escape the war and provide culturally appropriate programs for them rather than the military propaganda that dominates the media space. Donors should work with local media outlets to create children friendly programs and assist in increasing their ability to produce content that is original, educational, and promotes tolerance. Moreover, donors should also increase their support to local media outlets and seek to understand what Yemenis want to view. Ultimately, greater support to local media outlets, coupled with increasing the means and ways locals can exchange ideas in a neutral space, is achievable by increasing resources to both the readership and the professionals.